|

Front page exclusive in the Sunday Morning Post (2016)

The acrid stench of overheating plastic fills the air as a grime-covered worker perched on a bench surrounded by old printers nonchalantly tosses a cigarette to the ground. It’s dirty work disembowelling the detritus of the digital economy. Welcome to the New Territories district of Yuen Long, which if environmental campaigners are to be believed, threatens to become ground-zero for the world’s electronic waste. In recent years a cluster of legally questionable work sites have sprung up to store and dismantle the disgorged contents of the growing number of shipping containers arriving in Hong Kong from the planet’s biggest producer of e-waste – the United States. Monitors pile up, circuit boards are separated from smartphone cases and LCD screens are smashed to smithereens in scenes that are more Mad Max than Silicon Valley.In partnership with a Seattle-based environmental group that has monitored the flow of hazardous electronic waste out of the US for two decades, the Sunday Morning Post visited 10 such sites identified by the group using tracking devices planted inside waste products. The Basel Action Network (BAN) says Hong Kong’s traditional role as a transshipment point for mainland-bound e-waste is changing – bringing danger to not only the health of the often undocumented workers who break down the technology but the wider environment. Using coordinates passed on by the network, the Post visited sites pinpointed by hidden GPS trackers as the destination of US digital detritus. Seven of the 10 sites – all details of which have been handed to the Environmental Protection Department – were storing electronic waste.Three were hives of stripping-down activity by workers, few if any of whom were wearing protective clothing. At one site, which the Post was able to enter in the wake of a delivery vehicle, we found stacks of disembowelled monitor cases and computer parts. At least one of the discarded units carried a US postage label. A man in a sun hat told us “we dismantle things”. When pressed on what these “things” were, he denied that they were computer parts. “We’re very clean,” he insisted, before asking us to leave. Close to the entrance of another site within plain view of a Post drone camera were stacks of computer cases. Glass, rubbish, circuit boards and batteries could be seen among the gravel. A faint sound of drilling was audible towards the other side of the site, about half the size of a soccer pitch. A few metres away, under tarpaulin, four workers pulling machines apart with electric screwdrivers could be seen tossing remnants into plastic bags. No one was wearing protective gear. There were bags of circuit boards and copper wiring nearby, alongside piles of old laptops, some with floppy discs inside. Printers and scanners were also visible. An appliance marked with the logo of US home surveillance and entertainment technology manufacturer Channel Vision was found on the ground, alongside a US plug. “These are sizeable junkyards, and that’s a real concern ” said Dr Anna Leung Oi-wah, a biologist at Hong Kong Baptist University who specialises in the health and environmental impact of electronic waste.Leung visited the same sites earlier this year with BAN director Jim Puckett, who has been campaigning to stop the flow of hazardous waste from developed countries to the developing world for 20 years. There are also concerns about stuff getting dropped on the floor, or heavy metals getting into the water supply. And what about children playing nearby?Dr Anna Leung Oi-wah, Baptist University “Workers can get exposed to mercury in cathode ray tubes, lead is found in circuit boards. If they’re not wearing protective equipment they’ll be breathing in fumes,” she said. “There are also concerns about stuff getting dropped on the floor, or heavy metals getting into the water supply. And what about children playing nearby?” Of the 10 sites visited, two were deserted and empty, however remnants of e-waste, including circuit boards and fragments of LCD screens, lay alongside rusty nails. At one abandoned site broken LCD lamps – from which harmful mercury can leak – were strewn alongside an assortment of discarded computer parts. Surrounding these sites were rows of shipping containers, one of which with the help of BAN the Post tracked back to Long Beach, California, backing the network’s claim that as much as 90 per cent of what can be found at these work sites are US exports. One key fear expressed by environmentalists is the seepage of toxic waste into the ground, contaminating the food chain. A pig farm sat next to one site, a field of crops by another. In 2003 Leung and Puckett visited the Guiyi cluster of villages in Guangdong province, which had earned the dubious title of becoming the biggest electronic waste dump site in China – and possibly the world. They saw “mom and pop” workshops dismantling computers and melting down plastic in large containers using what they described as primitive techniques, exposing workers to toxic materials and contaminating the soil and water. Footage of the site shows blackened streams, and soil samples were found to be contaminated with heavy metals and other pollutants. The extent of operations at the Guiyi site generated intense pressure from activists and helped trigger a response from the mainland authorities who tightened controls on the importation of electronic waste. The crackdown made it much harder for e-waste to transit Hong Kong into mainland China and Puckett’s fear now is that – in part due to the city’s historic commitment to free trade – Hong Kong is becoming the dump of choice for e-waste exporters. A shrinking market and dwindling returns on old electronic components – which is driving an e-waste export boom – will only make matters worse, according to Puckett. In addition, the value of waste has slumped because fewer precious metals are used to make products. Hong Kong district councillor Paul Zimmerman says Yuen Long is a centre for e-waste dumping, dismantling, as well a smuggling hotbed for electronic and other used goods due to its proximity to the Shenzhen border. The activity has sparked fears over fire safety and the dangers of large trucks plying their trade on unsuitable rural roads. While the importation of hazardous waste to Hong Kong is illegal under the Basel Convention, to which it is a signatory, the city’s definition of what constitutes “hazardous” is allowing potentially dangerous waste to enter, Puckett said. A spokeswoman for the Environmental Protection Department said: “Non-hazardous e-waste includes main computer units, computer hard disks, other component parts inside a computer, printed circuit boards, printers and servers.” She added that the sites visited by the Post were under investigation. The US is the world’s largest producer of electronic waste – thought to generate 3.14 million tonnes of e-waste each year, according to the country’s Environmental Protection Agency. Hong Kong officials at the EPD have expressed their concerns to the US government. A spokesman for the US agency said: “We are in communication with Hong Kong’s environmental protection department on the issue of electronic waste management.”

0 Comments

Originally published in 2017 in the South China Morning Post (under a pen name... long story).

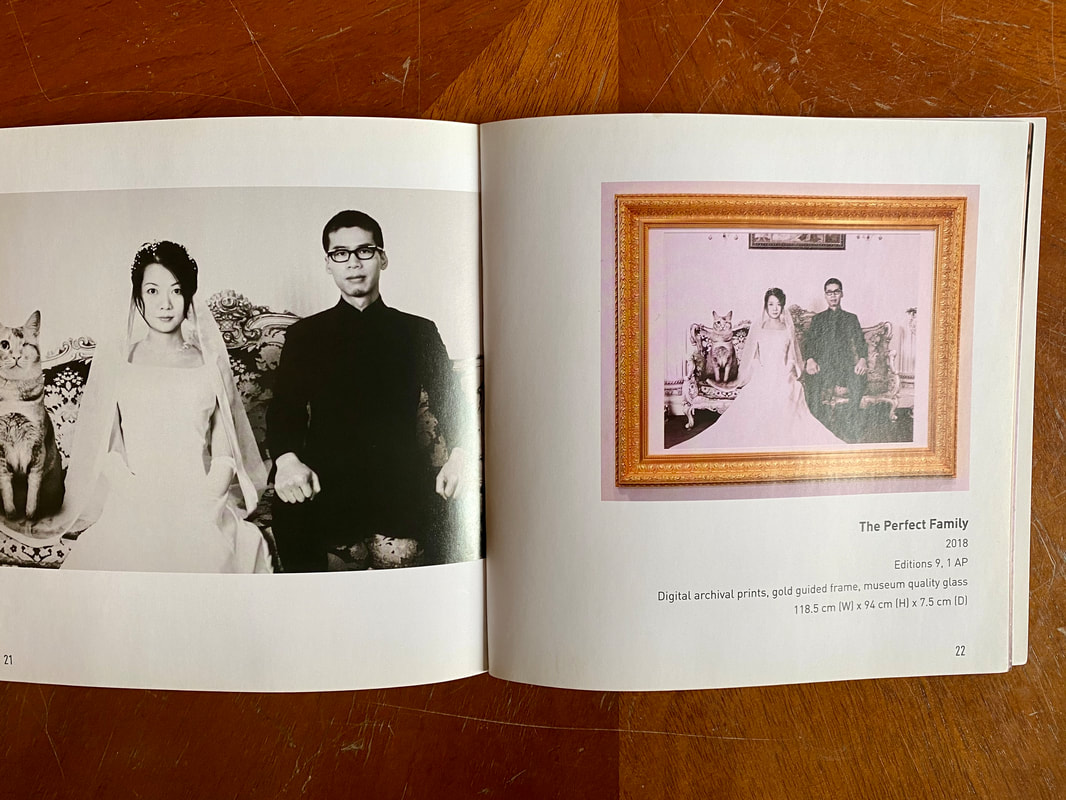

Off a dusty corridor in an industrial block in working-class Kwun Tong, a self-proclaimed spiritual guide, sells amulets laced with human bone fragments sourced from Thailand, and tends to her makeshift shrine. Children’s toys hang next to religious statuettes among droplets of wax and incense ash. An open box of pizza with congealed cheese lies on the floor next to fruit that has begun to rot: these are offerings to the ghosts and spirits believed to reside here. Hong Kong has plenty of ghost stories. With ancestor worship woven deeply into the social fabric of southern China, and real estate prices affected by fear of hauntings, belief that the boundaries between the living and the dead are porous is pervasive. The region has always been a melting pot of spiritual beliefs, with Thai Buddhist deities and Japanese atonement practices - a tradition of making a sacrifice to make right a wrong - incorporated in the very southern Chinese methods of appeasing ghoulish forces trapped in the living world. But Thai occult stores such as the one in Kwun Tong are a relatively new phenomenon, and one that is gaining popularity in Hong Kong. They offer a window into a murky, complex world of Buddhist and animist beliefs with a strong flavour of black magic. With a disarming smile, the spiritual guide – a Hongkonger in her thirties called Cat – pulls out one object after another from her glass cabinet. A golden amulet shaped like a skull with red eyes, a small tin containing a fragment of a human skull, a vial of oils she says were extracted by a monk from the chin of a corpse, a key chain with an illustration of a fetus on the front. She sells each object for upwards of HK$1,000. They contain spirits or ghosts that will help the owner move forward in life, she says. Some assist with matters of the heart; others bring financial success. Some imbue masculine prowess; others, feminine wiles. The logic underpinning the system is often karmic: save a lost soul and he or she will save you. “I first started seeing stores like these in Hong Kong in 2008 and 2009,” says City University anthropologist Thomas Patton, who specialises in the modern-day cross-fertilisations of Thai Buddhism across the region. “I’d say that’s when the industry started to take off.” Patton says he has seen about one such shop for each MTR station on Hong Kong Island. He hasn’t checked for any in Kowloon, but knows of a couple in Kwun Tong and Sham Shui Po. Hong Kong celebrities, including Jackie Chan, have been spotted wearing lucky Thai amulets. This was a factor that helped create a market for them in the city; prior to that they had only previously taken off to any large degree in Singapore. Patton says the Hongkongers most drawn to the world of amulets and Thai sorcery are working-class people hit by the 2008 global financial crisis. Businessmen, however, are also drawn to the practice, as are lovelorn women. People who like to collect things are also customers. “Hong Kong people have this obsessive-compulsive disorder over fetish-like things, whether it’s model boats that they like to play with at the weekends at the park, or drones ... or electrical gadgets and anime stuff,” he says. Whether all the Hongkongers who invest in occult objects understand their spiritual significance is unclear. With amulets available at phone and computer accessory stores, they might simply be a fad. However, the behaviours and values associated with these fetish objects classify as cultish, Patton says. A free consultation is required before any purchase at the Kwun Tong store. Like a therapist, the vendor will listen with empathy to your woes and determine which spirit is the most appropriate to call upon for assistance. Sometimes, she might not even prescribe a purchase: with a kindness that lends her an air of authenticity, she will give practical advice free of charge. Any purchase “depends on who or what you want to attract in your life”, she says in Cantonese, drawing upon the teachings of a Buddhist monk whom she sought out in Thailand. She gestures to pictures of him pinned to her wall. It is this monk who consecrates each object in the shop, she says, infusing in them the spirit or ghost enlisted to do the bidding of the new owner in return for redemption.She pulls out an amulet with an illustration of a mother and child. “This lady killed herself while she was pregnant,” she says. “The monk had to make many of these amulets” to ensure the woman’s tortured spirit had a greater chance of being redeemed with help from the living. The owner of the Kwun Tong store takes her doll Tung Tung out for walks and talks to it. Squeezed on a worn sofa are three men smoking cigarettes, fastening necklace chains to the occult paraphernalia. And in a leather chair sits a toy doll with an impish grin and penetrating plastic eyes. We are told that the doll contains the spirit of an aborted baby. “I used to feel sad about my life before I came here,” says a burly man in his 40s who works in construction management. He has joined the plastic doll on its chair, carefully balancing it on his knee and whispering sweet nothings into its ear. “Now things seem to make more sense and I feel better.” "I used to feel sad about my life before I came here. Now things seem to make more sense and I feel better" He says he comes to the store regularly, refers to the shop vendor as “big sister” and the people who visit regularly as his family. He speaks tenderly and pityingly of the toy doll, which is passed around the group for nurturing. For people who have trouble dealing with other humans, helping ghosts may be more straightforward and satisfying, even though Chinese tradition suggests staying as far away from ghosts as possible, says Joseph Bosco, an anthropologist formerly at Chinese University. Bosco has written extensively on supernatural beliefs in Hong Kong and China. “Traditionally, families left offerings out for ghosts, but did not interact with them so directly, unless with the help of some sort of shaman ... or Taoist priest.” That Hongkongers are dealing with ghosts in this way is also unusual in that, to the Chinese, when it comes to paranormal assistance there’s no such thing as a free lunch. “Some Taiwanese and Chinese have tried to get help from ghosts (such as help in picking lottery numbers). These ‘yin’ forces, however, will exact repayment in other forms; you may die sooner, or will suffer more in the underworld or in reincarnation. So any help the ghosts give is at a price.” Bosco says that while many Hongkongers will be put off by practices that involve close interactions with ghosts, there are several aspects of the Thai occult that appeal in Hong Kong and China. “It is precisely the fact that Thai Buddhism is both similar and different that makes it easy to incorporate into Hong Kong and Chinese beliefs. I’ve seen Thai statues of Buddhist gods in Hong Kong temples: they are viewed as new and more powerful, but fit into the existing pantheon and religious system,” he says. “Foreign” beliefs are commonly viewed as more powerful, he adds, mentioning gypsy fortune-tellers as an example. Associations with “primitives” – often viewed as being closer to nature – can lend a belief system a greater sense of potency. The lure of Thailand and its spirit world is not only drawing in Hongkongers, but also garnering attention further afield. “In 10 years doing research in Southeast Asia, I’ve seen more and more Taiwanese, mainland Chinese and Hongkongers coming in search of religious help for their business,” says Patton. There are Chinese arriving in Thailand intending to fill suitcases with amulets. With prices far higher online than in the Kwun Tong store, it’s big business. “Everything [has been] about the Chinese market, the Singapore market. Everything is just look look, look, money, money, money,” Thailand-based Briton Peter Jenks said in an interview with underground occult publication Rune Soup. Jenks has recently completed The Thai Occult, a book describing the beliefs to non-Asian collectors. He says there’s been a ripple effect of interest in Asian spirituality in the West, from tai chi to far more esoteric practices. Thailand is a particularly strong magnet for seekers of the supernatural owing to its complex ghost world. “Most aspects of life [in Thailand] have a magic aspect – there are spirit houses attached to every dwelling,” he says. According to Jenks, the boundaries between life and death in the kingdom are incredibly thin. In the Kwun Tong store it is approaching midnight when we leave, having bought nothing but been offered information for hours, an invitation to return at a later date, and a tacit warning: it gets a lot darker than this. In 2018, while I was mostly working as art editor for a long form culture and history magazine focusing on Hong Kong, I was asked to write the introductory essay for an exhibit held in a gin bar showcasing the works of artist/activist Kacey Wong, whose art and ideas I later covered while working briefly as Hong Kong Free Press's managing editor. You can read that piece here.   |

AuthorSarah Karacs is a journalist, Archives

May 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed