|

How to bounce back from bodily rebellions: Our research-addicted writer's ongoing workbook.

Another one of those quirky dreams struck the other other. I was wandering around a dimly lit Norwayville-style toytown without teeth. There was an operation I was meant to be at to get my face fixed that for some reason had been missed. Rather than resolve the problem I had instead chosen to wander the streets forlorn and despondent. Quite sure there’s no symbolism to be gleaned here at all. If life is about choices, a lot of them still seem to be made entirely by my body’s visceral reactions to how I’ve been treating it. After a relatively heady but also stressful month, my body revolted in its favourite way. My “moon cycle” as the hippies call it, announced itself with a level of brutality that had me vomiting up painkillers all over my balcony after a night of agony I’d gladly swap with being pummeled by a Muay Thai fiend. Time to clean up my act, apparently, and clean out my system. Out with the late nights and enraptured conversations with people I’ll probably never see again, in with the nerdy focus on health protocols, energy systems, cortisol levels, early mornings and exceptional sleep. Along the lines of saying “yes/no” to a variety of things, I experimented with a fast that lasted four days, and slept very well. “And what about your performance?” asked my training buddy who had scheduled a hefty mix of hack squats and trap bar deadlifts alongside all sorts of uncomfortable lat-building exercises. This was a few days after the fast ended. Well, I guess I had lost some strength. But what is apparent is an improvement in cardiovascular endurance (or maybe just a lighter-footedness?), which I think is something I value in a way that she’s not so concerned with. This is because I associate it with giving me a greater resilience in bouncing back from stressors that might otherwise have floored me. Still, if I truly wanted the engine back that I had in some points of Corona -- when I wasn’t smoking at all and when I was out running most days, had a limited social circle and lived comfortably with my nose in a lot of books -- I’d have to go all in and throw my cigarettes out of the window. The logic obviously goes that in order to do away with a bad habit, you have to find a replacement for it. Meditation or breath-work, or even punching Nigel, could work. (Nigel is the heavy bag that lies on my floor wearing a jumper with arms I’d stuffed a few months back so as to practice submissions). But sometimes this isn’t really enough. Especially when trying to put yourself through your own regimen of exposure therapy so as to refrain from doing a Hermann whenever life hits you: I.e. running away and finding a hole under a kitchen cabinet replete with all your favourite shreds of toilet paper with the aim of living there forever. A concluding sentence is required here: but the reality is that I don't have one. Just need to keep pushing my limits and learning to regulate accordingly.

0 Comments

In which our hitherto reclusive writer resolves to Get Out There, master the drunken bench press and say no to unnecessary drama.

Berlin summer is in full swing again, but this year, everything feels quite different. This summer, Berlin has come alive. Everyone is eager to get out and about, the rats especially. The furry and plump renegade that he is, Hermann has committed himself to several break out attempts, his most devious being enlisting Kotti in a misdirection plot that had me chasing both around our odd little vampire-inspired apartment in a nightgown like a lunatic straight out of a gothic novel. Hermann has found a hole under the kitchen counter that he’ll retreat to, victorious, for several days, until hunger humbles him enough to return to his plush cage where the usual choice selection of mascarpone and seasonal vegetables awaits. Sometimes, if he’s feeling especially rebellious, he’ll pull apart a roll of toilet paper and carry its shreds into his man cave with him, and I’ll leave a bowl of water out to show that we’re still friends despite his endless mutiny. I worry what will become of him if he carries on like this, though. Beyond the confines of our testosterone-addled apartment, which has for various reasons been overrun by Irishmen alongside male rats for the last couple of months, I’ve noticed a number of graffiti tags across the district with the single word: “rat”. I am assuming he has found a gang of fellow miscreants and I wonder whether I should start saving up bail money should he get into real trouble. Still, I have taken a leaf out of Hermann’s book and resolved to plot my own Berlin adventures to offset the years of confinement that came with pandemic life. I am trying to be a “yes” (wo)man. That is, finding excuses to say yes to the outside world and all its invitations. That has meant: yes to: improvisational jazz concerts helmed by a friend who’s a wizard on the synth. Yes to trekking to an abandoned factory in Steglitz to help build an enormous perspect eyeball headed for Burning Man and dreamed up by a neuroscientist. Yes to boozy dates that descend into drunken bench pressing or fussball tournaments in which, I’ll admit, I perform pretty well. And yes to being wide awake, and excited to meet the world in all its technicolor wonder with the downside that saying yes to somethings ultimately means saying no to other things. Like good sleep, and happy, tobacco-free lungs. When my mentor, Joyce, coaxed me into taking that newspaper job in Hong Kong all those years ago, she did so with the line “life is about choices”. One area of my life that I’m experimenting with saying “no” to is the world of conflict. Let’s not overcomplicate this or politicise it. Having initially resolved to commit myself to a summer of martial arts practice, I did a 180, and decided to see what happened if I avoided conflict altogether. As in, point blank, didn’t register it even when it was glaring at me in the face and taunting. This was inspired by how my training buddy, a gorgeous, statuesque German with a fascination for the bodybuilding world handles small annoyances like having plates rudely claimed without our consent at our gym’s squat rack. “If someone is rude to me, I just *blows them a kiss*. See, if I get angry at them, it shows that I care what they think. It’s better not to care about what they think.” She’s honestly my hero. In the absence of martial arts, I’ve -- physicality nerd that I am -- now, doubled down on the other training modalities that have helped manage my moods and energies for the last four years. I temporarily took a break from CrossFit and tried out simpler HIIT formulas. Some of these involved heart rate monitors that proved something I probably already knew: I have a strong and resilient heart which I’ve learnt to control with my breathing so as to manage a severe anxiety disorder. The strong and resilient heart is genetic, I think. The last time my VACCINATED 67-year-old mother caught COVID, she still went skiing (even though I told her not to…) and got in about 12 k without much fuss. The funny thing about HIIT and heart rate monitors, is that the name of the game is actively raising your heart rate, which is the opposite of what you want to do if you’re trying to circumvent a panic attack. So it feels counterintuitive if you’re used to using sports to manage anxiety. However, through trial and error, I found that deep and intense -- but still controlled -- belly breathing mid-sprinting does raise your heart rate such that you can “win” the heart rate monitor game you play during HIIT, while maintaining a state of calm. Anyway, with that specific problem solved, I’ve returned to CrossFit, which, to its credit, poses slightly more complex fitness problem solving games without having to get punched in the face. The real problem that lies in front of me, now, is, how do I say yes to optimal movement, without having saying no to optimal other things? Our writer adopts a pair of lovely rats, and meditates on politics, power and precarity.

Two perfect angels moved into Dracula’s mansion last week. When I say angels I mean rats. The transgressive and withdrawing Hermann and the convivial and attention-seeking Kotti. They are named after two U bahn stops near us. Their human had regretfully placed them in my care having developed an allergic reaction to them. She loaded me down with their plush blankets, a pot of their favourite treats and their multiple toilet trays. She also warned me not to give Hermann too much coconut water -- it’s making him fat -- and not to smother them. Rats like doing their own thing, and, like cats, prefer to approach their human for affection as and when suits them. After spending the day running around the flat, which is now filled with all sorts of rat toys, they retreat to their elaborate cage to munch on greek yogurt and muesli and nap in a hammock I wash each week. Perhaps there’s a comment to be made here about the gentrification of pets. I don’t know. The more pressing point to make is that rats make excellent company. Even Hermann, whose intrepid spirit means we sometimes wind up playing a prolonged game of hide and seek in which he always thinks he’s outsmarted me -- even when he’s tucked under a pile of clothes with his tail poking out (“nothing to see here, lady”), has scampered his way into my heart. Kotti likes to have the side of his face stroked, this is heaven for him. And if I’ve been out for long, I’ll come home to find him pressed against his cage waiting for a greeting. I put my finger through the cage once, and he reached out with his little hand (hands, not claws) placed it on my nail, and looked into my eyes. When I give them treats, they take them so politely with both hands you’d think they’d gone to butler school. Ludvik Vaculik's Guinea Pigs Caring for them has made me think of a Czech novel I studied at university. Ludvik Vaculik’s The Guinea Pigs is a dark comedy set in Cold War-era Czechoslovakia by a dissident writer. Here’s a passage: “The hardest thing in the world, girls and boys, is to change your life by your own free will. Even if you are absolutely convinced that you're the engineer on your own locomotive, someone else is always going to flip the switch that makes you change tracks, and it's usually someone who knows much less than you do.” It tells a story of a banker living under the absurd and hopeless conditions that characterize corrupt authoritarian rule. As an escape, he turns to his pet guinea pigs for solace. He takes refuge in their vulnerability, in fact, it empowers him. He finds himself playing games with them that help him feel powerful where elsewhere he is powerless. At one point, he finds himself, well, waterboarding them: “Take a paper bag, place it open on a table and let the guinea pig crawl inside. Then twist the bag shut, just so the air can get in, and go to the movies. When you get back, you'll find everything just the way it was when you left. Take a glass, fill it with water, then change your mind and pour the water out, and take the glass and turn it upside down over the guinea pig. You can observe the guinea pig through the glass walls, watch it sit there in astonishment, its nostrils quivering in excitement, its tummy undulating nervously, and yet it doesn't even try to determine the penetrability of the wall around it, at least not during the first hour”. Monkey see, monkey do. Especially when it comes to the exploitation of power. Nightmares about war The day I picked up my rats from their human, she told me she’d slept badly that night. She’d had a nightmare about a war she’d have to fight in. I’ve been having nightmares too. An elaborate one about trying to stalk down a murderer who was after a friend of mine. Another in which my teeth are pulled out. One counting dead rhinos, a whole field of them. I have a friend in Russia who is eight months pregnant. I send her pictures of the rats doing silly things and she responds with hearts and kisses. It seems crazy to think that not even a year ago we were walking through Tempelhof together talking in German about how much we liked foreign languages. She was planning to learn Arabic. I agreed that the script is beautiful. She’s one of my only Russian friends. Another one once falsely described Chopin as Russian. She backtracked very quickly when I pointed out that he was Polish. That was the end of that conversion. We quickly went on to discuss how great corgis are -- a far more comfortable conversation. My own family history means that I’m wired to mistrust the Russians, it’s been a bias I’ve had to work on. I view pictures of the Kremlin the way my Hong Kong friends think about Tiananmen. Creeps me out. So I’m not as shocked about the decisions that have been made within the Kremlin by a certain steroid-addled gnome-faced freakshow as maybe others are, but I am of course horrified. I went for drinks last week with a journalist friend from New Zealand who's been covering the Middle East beat for almost a decade, so she is not surprised by the level of brutality that has been on display. She took in a Syrian sniper a few years ago, when she asked him what made him join the resistance. “It was a gradual thing. He didn’t think he would fight initially, he just joined the protests. But then he did,” she said. The righteous indignation made him take up arms. “I was thinking, if the war came here, would I stay and fight? I think I would,” she said. “Would the Germans, though. Would they stay? Are they ready for something like that?". I don’t mean to be alarmist, and I’m not interested in making any predictions about how this war will end and what role average Europeans outside of Ukraine and Russia will play in it. As a reminder, few people predicted the fall of the Iron Curtain in ‘89, that deeply traumatic event for Putin. A new precarious era I think the fact that this horror feels closer to home than most Europeans of our generation are used to is worth examining. These are the conversations we are having as we enter a new era of global uncertainty and precarity, and in which the faultlines of authoritarianism versus democracy have been clearly drawn. If it came to it, would I stay and fight? Like those Ukrainian women cutting down their lacquered nails to hold AK 47s? I know I’m in the physical shape for it. But the mental game? And the threat of rape? Let’s move to another topic. A clip from a female Ukrainian politician who has stayed to fight plays out in my head a lot. She talks about going to bomb shelters and teaching children to “drop down and play turtle” when the siren goes off. “What our generation wanted was for our children to grow up without trauma. We failed them,” she said. I went for drinks with a group of non-Europeans this weekend, hoping to get a break from the doom scrolling. We were in a very Berlin bar where burlesque dancers poured hot wax onto one another and complained about a meddling neighbour trying to shut them down. An American had been saying that, if push came to shove and they needed to get out of Europe, Central America would be their exit strategy. Imagine that. Leaving Europe for the safety of Central America. Eurocentric coverage? “I’m sick of how Eurocentric the coverage has been,” said another friend of Asian descent. These were words I didn’t really want to hear, given how painful the last couple of weeks of witnessing have been. But there is a point there, too. Living without the precarity of a looming war (with, albeit, the threat of the looming climate crisis) has been a privilege here. As has living with the assumption that freedom can be taken for granted. That was something that really depressed me when I first came back to the city two years ago, having witnessed Hong Kong’s bitter fight for freedom. That’s changed now, at least, perceptually. Nothing can be taken for granted. A historic vaccination enters our writer's bloodstream.

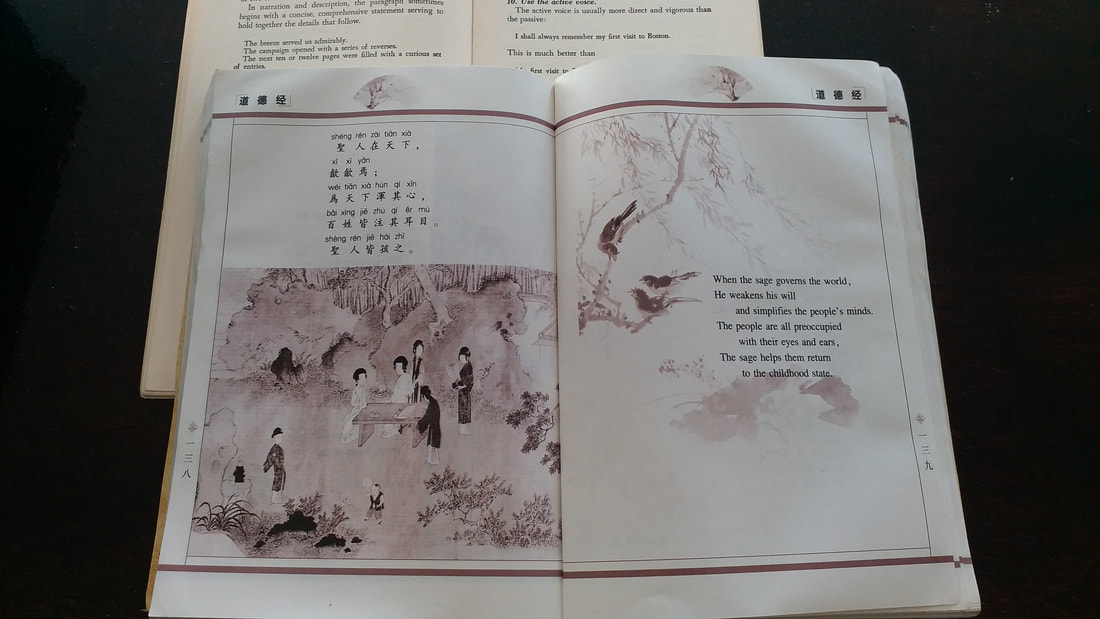

A great triumph of science entered my bloodstream last week, an event that involved the bizarre, post-apocalyptic experience of entering an ice-skating stadium turned makeshift vaccination centre and being told off for taking photos of men in army suits. ‘It’s a historic moment,’ I told the nurse who stood over my shoulder and made sure I’d deleted each one. I was surprised by the extent to which my body reacted, its weakness, and the strange fever that followed the night of the vaccination, in which I’d dreamt of my brother strangling me. It’s one of my most recurrent nightmares, but this time had the twist that I’d fought back. I’d had assignments that week -- interesting ones -- and was annoyed by the slowness of my mind, worried that attempts to preserve my sanity through lockdown had dulled the critical faculties I need to perform well professionally. Sometimes, it feels like when you turn a light on too bright you don’t notice the cobwebs you’re supposed to as a half decent journalist. I ask myself the question - In making concerted efforts to be happy, had I turned my back on my own intellect -- and at what cost? And where’s the middle ground between living a life of joy, and a life of purpose? I’ve been making concerted efforts to follow and scrutinise the news again, properly, and in German, writing out each unfamiliar word as I used to, back at university when the fear of blowing up my brain had no hold over me, when everything was a frenzy of learning, and where everyone was unapologetic in their love of knowledge, complexity and of depth. And more than willing to put up with the discomforts that came with that sort of cognitive stretching and scrutiny. But now I’m romanticising a time that was also really challenging, and an environment against which I’d actively rebelled sometimes, too. Seems like wherever I am, I find a way not to fit. But maybe that’s just where I’m meant to be. P.S. I'm towards the end of Ferrante's Neapolitan Quartet, and it's literally the best thing I've read in five thousand years. Highly recommended. In which the writer marks her first year back in Berlin with a foray into the colliding worlds of myth and reality, I celebrated completing my first year back in Berlin this week, marked the occasion with a remote call with the two friends – Ben and Alice - who had felt most like 'family' in Hong Kong –beleaguered but kindhearted journalists from my old newspaper who also happen to be some of the wittiest and most cynical people I’ve ever met. I gave them a tour of my new place, an eerily charming and quite expansive space with creaking floorboards that I discovered via the city’s journalism circuit. Here, chandeliers hang from high ceilings, an 150-year-old ‘atmospheric’ sounding piano complete with candle-holders stands next to a full-blown walk-in bar of dark wood and faux-gold furnishing and a beer tap that appears to only serve aesthetic purposes, as black-and-white illustrations and maps showcasing the Berlin of yesteryear abound. A panel of blood-red wallpaper completes the look. Lighting is quite low, so many of my evenings are accompanied by the glow of candlelight, placed next to the large, fat-stemmed and rather mysterious purple and white flowers I bought. I've left their fallen petals to wilt. A luxurious enough experience can be had lounging on the baroque-style, sheepskin-rug-bedecked sofa overlooking the hinterhof complete with trees that now sulk with their forlorn and jagged winter nudity, though the highlight of the space can be found in my bedroom, which is certainly more regal than any I’ve ever occupied and which overlooks a rather quaint graveyard. In self-help books we’re told to create a visual image of who we most desire ourselves to be. I’ve always had this picture of myself, feet propped up at a vast and powerful-looking desk complete with pillars of of books and papers, with a cigar in hand. This desk here comes close to that visual, though it’s of a rather grim and haunting dark wood that exudes undead vibes. “You’re renting from Dracula, aren’t you, Sarah?,” Ben says. I wouldn’t say Dracula so much as I feel like this place resonates more on a Huysman level. Huysman’s book Against Nature (À rebours) was one of my favourites at university, a recommendation from a tutor who always knew exactly what I needed to read, a rare talent that never goes amiss. Looking it up now, I find a version of an early translation in which its first page opens with the subtitle "A Novel without a Plot". Brilliant. Novels without plots, plots without novels Against Nature (described in on review I read as “one of the strangest books ever”) follows the eccentric Jean des Esseintes– the last scion of an aristocratic family– as he shuffles wearily around in a robe rarely leaving his luxurious but somewhat haunting home bemoaning the modernity and chaos of the outside world, entertaining himself with classical French and Latin literature of specific eras (the only good ones, he insists) and the companionship of a tortoise who he inadvertently kills when he sticks jewels onto its shell. As students of literature we are taught to think about the messages characters have for us in the present day. The book was written in 1884, and des Esseintes is presented as a relic of a bygone time, having retreated completely into a world of fiction he believes far suits a person of his lineage in an age of social and technological upheaval. (In 1895, by way of example, the Lumière brothers — pioneers of film — produced a short movie of a steam train roaring down a railroad, which marked the onset of the moving image, to name one major development that brought about the rise of mass culture). Des Esseintes is an interesting character to think about for a number of reasons, not least that if he lived today and had assess to Wifi, I can see him as one of those anonymous internet troll decrying all sorts of things in a last ditch effort to maintain a semblance of relevance ('to feel heard') In a world in which he can't keep up. (#notallaristocraticscions) The character also has a rare and specific "decadent" illness not without overtones of vampirism (a spectre that best symbolises these old-world/new-world clashes and fears that Decadent literature so evocatively explored). He is sickly and prone to sensory oversensitivity such that, in fact, books, books more books accompanied by the strange orientalist gongs of the so-called "East" that he has farmed in from worlds he has never seen (Said eat your heart out)– suffice in sustaining his creativity and enjoyment of life such that he never need step outside, nor seek companionship at all). Some people seem to think the onset of new technologies like AR and VR will turn us all into Des Esseintes. I am not ruling out the possibility. But it should be said that humanity has been inoculating itself against the realties of the world through fiction for millennia. We've always had access to that form of escape – the more shrewd humans among us have always found ways around the mythological noises that take us off course from the truth, however enchanting (and in many cases, rewarding) these meanders might be. A globetrotting granny Sometimes when I think about Des Esseintes and the question of fiction as escape (versus fiction as freedom), I think about my grandmother, a singular and cerebral working class woman who decided quite early on that the likelihood of finding a man who would show her the world she dreamed of seeing was quite slim in sleepy Tunbridge Wells. So in lieu of the pursuit of a husband she taught herself five languages and worked as a secretary in a multinational organisation. She met my grandfather while she was working in Vienna. Her marriage to the Hungarian Calvinist of Transylvanian roots was short. Some years later, she had an affair in what is now the Republic of Congo, but if I am correct spent her longest stint in the city that agreed most with her besides London: Paris. This is why I have a half-Malaysian half-uncle with a Hungarian surname who speaks French like a Parisian. If there was one thing that charmed my grandmother more than travel and the promise of new worlds, it was the world of ballet. All she wanted to do in her retirement was attend every dance institute in the area. She was probably a patron of more than she could afford, might have single-handedly kept many open. She lived for these fictional worlds, they sustained her in a way the real world couldn't. Conversations over the phone always centred around that season's theatre and dance programmes, and I was supplied with more novels from her while I was growing up than I knew what to do with. Of course she was the person who gave me my two favourite books from childhood: Little Women, and Chinese Cinderella – the latter being the work that sparked my own dream of globetrotting adventures I eventually realised (an event in which myth collided quite rudely with reality). Prone to falls and incidents one assumes come hand-in-hand with being rater bookish and otherworldly (as opposed to robust, coordinated and grounded), my grandmother approaches her 90s with a surprising lucidity and promising bill of health, despite having always been too "something or other" for this world. Smart, maybe? This said, she has recently moved into an old people's home, a confronting experience which has inspired some of degree of myth-making on her part. "These women are all prostitutes or lesbians!" she has said on one of those days she has in which her grip on reality is less strong. But anyway, back to Against Nature. I love the symbolism and the haunting hopelessness of the work, it's so eerie and meandering and mystical, captures the sort of total retreat into introspective god-knows-what-world that can happen to some circles during times of seismic change. That poor tortoise. To hammer down my point: In the words of my best friend from school, Ceyda: “I hate Trump because he totally took the fun out of conspiracy theories”. It's true. The fun has been taken out of myth-making and risky meanders from the truth. Our other school friend, an artist-turned-social worker specialising in drug addiction –who is my best source for understanding London's increasingly worrying crystal meth scene, (alongside the best confidante I've ever had), no longer sends me bizarre articles about airports designed by the illuminati from 'Vigilant Citizen,' the website that also inspired some of her weirdest illustrations. Our WhatsApp group is still riddled with snapshots of Occultish dolls and Victorian taxidermy fails, though. She most recently reports a great time to have been had at her virtual 'Moon circle' retreats, an activity she squeezes in between virtual gong baths and sobering phone calls with clients from all walks of life, and phone calls with me. Last month, when I was struggling with a greater degree of emotional disturbance than felt manageable at the time, I spoke to her about wanting some kind of emotional vasectomy, something that could efficiently remove these feelings from me so I wouldn't have to bother with them. "We all want that sometimes, Sarah. That's literally why people take drugs," she said. To return to our main event But, actually, my understanding is that, the previous tenant here was not Dracula, nor an aristocratic scion-turned-nutty-mystic, but a rather jolly German man who, according to neighbours, was prone to noisy, convivial late-night antics. “You mean sex parties?” Ben queries. Possibly, who knows about the stories that came here before mine. “I’d love to see you at a sex party,” Ben adds. “Standing politely in the corner saying stuff like ‘how nice it is we all get to spend time together like this.” The neighbourhood is quite different from the one I recently left. On my evening walks, which have now transformed into evening runs –the time of my day in which I feel most alive during these bizarre soon-to-be-mythologised, socially-rupturing lockdown times, – I am far more likely to bump into a drunk than a pram-wheeling lady holding a chia seed smoothie. One practise that continues here, as it did in Prenzlauer ‘pregnant lady’ Berg is that of people leaving items out for scavengers such as myself to root through. I’ve always enjoyed accumulating other people’s things, especially when their story is mine to try and interrogate, bring to life somehow, create fictions in the between spaces of their cracked realities. I now own a scratched gold watch, a flamingo figurine, a pink teacup and a forlorn and slightly ripped photo of someone’s dog, among many other decaying oddities. I’m not sure what to do with any of it but I am glad they are here in this, in this hall of dark, enchanting and zany things during these strange, long months –ready to recycle themselves out of their oblivion into some new story, a decadent meander between fiction and truth. Yours, Vlad the Impaler x. p.s. New (O.K, recently rediscovered #content uploaded elsewhere)  Just off Hermannstrasse, Neukölln Just off Hermannstrasse, Neukölln In which the writer has her work critiqued and as a result offers her reader a greater deal of context. I have recently shared one of these posts with a writing partner whose feedback was as follows: “It’s the rambles of an ‘impossible’ narrator who provides no context.” I suppose there is some truth here. An editor once made a similar remark about my writing: “It takes you awhile to get to the point.” He echoed much of what I heard growing up, trained under the maxim that everything worth saying can be whittled down to a headline, and that all headlines that stretched beyond two lines were a disgrace. That everything halfway from here to there says nothing at all. There was news. And there was dross. And then, there was the perfect headline. Why could I never write the perfect headline? Why do I still struggle in writing the perfect headline? It’s never quite there. It’s always short of that one word that I can’t access, that’s sitting just on the tip of my tongue. Somehow that perfect New York Times-esque balance between punch and elegance eludes me. There was news, and there was dross. I edited myself accordingly. Kept quiet the places I did not know. Listened for a clarity that never came. Now I wonder whether these meanders into nowhere and everywhere are my own rebellion. But here: some context: When I began these posts I pitched myself to my invisible audience as a so-called “third/culture/kid” having returned after years of timeawayness as a journalish-daughter-of-a-journalist relocating to a city I once knew fromchildhood. Along the way I have described the ethical quandaries, the pain and relief of leaving Hong Kong during its depressingly historic moment, I have gone into the various emotional and intellectual quagmires of my trade, and I have also taken little forays into the world of MMA that had served as a much-needed escape and which helped me learn to embrace parts of myself buried deep underneath all this excessive thinking and analyzing and worrying, and this unshakable, maladaptive perfectionism that always burns me out. On the mat, I don’t have to be perfect. I just have to be game. “Stop thinking about what you can’t do, start thinking about what you can,” my first coach used to say. Through this time, in which I went from staring bleakly out of windows, and partaking in my favourite pastime, that is, walking wherever my feet take me, new responsibilities came my way, not least a fellowship inviting me explore Europe’s shifting media landscape, and so have various shifts within me taken place. I can’t say I myself have achieved a sense of belonging here (I am doubtful as to whether that would happen anywhere). But I believe I have found my feet. And I am getting a little bit closer to achieving one thing I set out to do: Be imperceptibly foreign when I open my mouth. Last week, someone mistook me for a Bavarian. I consider this progress. More context: I would pretend that I had bold plans for this little, aimless project of mine. But really it was to help keep my fingers busy and my mind active through Corona, and because writing is always what I do when I need to figure things out, and returning to Europe after all these years away has been one of the strangest, most necessary things I’ve had to do. Bounding into the unknown has always come far easier to me than homecomings. There is your context, kind, invisible reader. Oh, to explain another point: I have entered into the habit of beginning each entry by describing the view outside my window: A warm up for my fingertips that reminds me of an early premise made here: That a change in perspective might resolve certain feelings of restlessness in looking at something that seemingly remains the same. I observed seasonal shifts from my window, tried to interrogate my view in a way that would prevent me from growing bored of it.

But I also cheated in this exercise. I have moved twice now since I began this blog, and I still can’t escape my geographical restlessness, much as I know that staying put, creating routines and a sense of familiarity and attachment, are what I need to do to find the roots that elude me. This new view is so far my favourite. Especially at golden hour, which it is right now. I’m not sure I’d appreciate autumn so much if I hadn’t lived without it for so long. Read more on Sarah's Mixed Martials Arts journey via the links below: 1. Fight Club 2. Lessons from the mat 3. Good and bad algorithms 4. Taming the lizard brain Read her summary of why she fights, and what cultural value MMA brings in her BIO.  In which the writer makes an inventory of the bruising inflicted during a particularly passionate week of fighting and learning. Early morning. Birds moving mostly in one direction, brown has overtaken green and leaves jitter. Visually, winter’s approach is palpable. Physically, also. I wear woolen socks my mother knitted. My feet still feel a chill, but it’s fine. The sensation wakes me up, keeps me alert. These are in fact the perfect conditions for writing. Mild, austere discomfort, and quiet. As I take this inventory of subtle hallmarks of a seasonal shift, I notice changes that have occurred in my own body this week, too. A greater determination and focus has seen me commit more time to the mat, and the ensuing improvements in performance have lead to me taking greater risks, and showing more tenacity and confidence in a fight: Has led to me showing up, in a fight. Working actively, not just reactively. Though my hesitance in committing to a takedown pervades. I continue to opt for the process that has worked time and again: Keeping low, letting my opponent execute the takedown, and allowing my body to do what it often seems to do of its own accord in this particular context, that is, somehow land and flip things around such that I end up having the upper hand. “You always fall on your feet,” my mother likes to say. This shift in tenacity and confidence writes itself into my body. My shins, first, are peppered with subtle green and purple bruises, and there’s a cut on my ankle proving that a sparring partner has not abided by the rules and forgotten to clip his nails. These mementos don’t feel all that strange to me; anyone athletic or outdoorsy would have them. And they remind me of a session we had with my first coach and his motley crew of fighters who were, by the way, some of the loveliest people I’ve ever met, and besides journalists, the best community I’ve found in terms of being able fling this way and that some great zingers. (‘Go read Moby Dick, nerd’ one guy used to shout at me, before demanding I make him a sandwich. Of course, I lined up my own retorts, and fired them in his direction in between rounds. He, a serious gamer turned Muay Thai nut, was a super fun guy, and I really miss him.) But yeah, this session I was reminded of, in which our coach told us to stand in a circle and commit to a chain of low kicks, going round and round, learning to instinctively twist our thighs around and tense up the muscles as we received the kick. “You just have to build up resistance to getting kicked so you can focus on other things during a fight,” he said. You learn to laugh off the pain and see bruises as essential to the learning process. The further up my body these bruises go, the stranger I feel about them, the more I feel like they ought to be hidden somehow. What would people think if they saw them: The purple patch around my wrist the size of my palm which speaks to someone’s attempt to get me into an Americana which I resisted by tensing my bicep, sliding my other hand under him, creating leverage, and clinging to that endangered hand as I slivered out from underneath him. “In this session, would you like to talk about why you like to fight men?” a therapist asked me last year. The answer to that question is, if given a choice (class ratios tend to be 10 per cent women, if that); my optimal opponent is a woman who is just a bit stronger (doesn’t happened all that often, I have to say) and more experienced and knowledgeable than me (happens all the time). This is optimal for learning. The women I fight with, on the whole, tend to be more communicative and gracious, and the experience of being dominated by one tends to stir fewer complex emotions in me. Although I am getting better and distinguishing between the male opponents who want an interesting and challenging fight, and are helpful and cool, from those that, it seems, really struggle with the idea of being overpowered by a woman, and who can get carried away when that prospect presents itself. I can feel it, when those emotions come up in them, and something in my body prepares accordingly. I sharpen, and focus, and something within my chest jitters like those winter leaves, almost impalpably. I operate entirely in a defensive mode and play a long game. I try not to tap out in fear, and I try to get the upper hand as and when they start to gas out from all that huffing and puffing. I protect my wrists. Because these are the guys who especially enjoy a nasty wrist lock which disables you quickly with a sharp, searing pain. A cheap shot. Most importantly, I stay put. I don’t run. And at the end of the round, I shake hands/ bump elbows, and look my opponent steady in the eye. I’ve been told, by women, that the guys you need to watch out for are the ones who show up having watched a bunch of YouTube videos, eager to fling their weight around. Dedicated guys are not really about that, they say. “You know, if it was easy, I wouldn’t keep coming back,” said one guy this week, who taught me two new submissions and to whom I admitted struggling with these complex maneuvers. It’s true. If it was easy I wouldn’t keep coming back, either. And I feel exactly the same way about facing a blank page, too. If writing was easy, I don’t I’d do it so much. There are other bruises, few of them I remember the specific event in which they were inflicted, and which I certainly did not feel as they were inflicted: An ugly and heavy brownish purple one on my arm that has faded surprisingly quickly, and a big annoying purple one on my right elbow that makes itself known every time I attempt to rest on it, and which made me jolt slightly with pain during a meeting in one of those strange moments where the professional persona you have is rudely interrupted by the person you are in your other worlds. Creep higher up my body still and we have something that has never occurred as a result of my recreational activities before: a little bruise on the side of my chin which I would cover up with concealer if I could be at all bothered with applying make up on a day-to-day basis, and a nearly imperceptible scratch on my left eyelid.

This reminds me of a great line from my first coach when he returned victorious from a fight in preparation for which he had had to cut 10kg of weight in under a month while studying his opponent – a kickboxing brawler-type known for his unpredictability in combat. “Still pretty,” he said, on his first day back, pointing at a face that was almost blemish-free. In an interview with The New Yorker, Ronda Rousey, MMA’s (now retired) golden girl (whose face is also blemish-free) said that it was the girls who didn’t look like they fought that you had to watch for. They were the ones who were good. The woman who played a part in coaxing me onto the mat with the line; “I can’t wait to see your first KO” - Hong Kong’s first female professional MMA fighter, who quit her high-powered job in management consulting after smashing up too many computers, also didn’t “look” like she had fought. Some might read the anecdote above as an indication that the person probably most responsible for this strange hobby of mine had anger issues. This simplifies who she is, and what learning to fight does for people like her, people like us. I think some people in this world are racehorses trained to work in pony pens. Intense emotions, like anger, are symptoms of something underlying, something that is wrong, and that needs to change. It’s the lizard brain screaming “enough!” – the part of yourself you learn to talk to, negotiate with, and tame, on the mat in way you don’t get to anywhere else. Not even in a therapist’s chair. I am not sure I can call myself a racehorse. I believe I am little bit too awkward a person for that label. Racehorses are so suave. But what I am doing is operating within a lane which is quite different from what it’s “supposed” to be, and I think what martial arts is helping me do, is find the courage and the tools to commit to this path. And the result is I have a life I love, bruises and all. Read more on Sarah's Mixed Martials Arts journey via the links below: 1. Fight Club 2. Lessons from the mat 3. Good and bad algorithms 4. Taming the lizard brain Read her summary of why she fights, and what cultural value MMA brings in her BIO. In which the writer resolves to foster calmness so as to make wiser decisions on and off the mat. It’s late evening again, and I am pulling shards of glass from a mirror I accidentally broke earlier this week off the rug, listening to weekday traffic gliding home, squinting to see a blueish grey sky through a pair of glasses so clouded I really ought to replace them soon. I wonder when I write these things about the extent to which characters besides myself should get their airing. I struggle with this, the personal and the journalistic slipping and sliding between one another. It is an uncomfortable place that I do not like very much and where I try to tread lightly. That I returned to the mat might be evident. A couple of points to note, that I think might be relevant to some of the themes explored here. First off, that film of fear and/or adrenaline I had been carrying onto that, and mats before this one, has evaporated. I bring a calmness to the study of conflicting bodies that has eluded up until now. I think I might owe that to having spent the last months doing very little except staring out of my window and going for long, lost urban walks, in what has been one of the only times in my life in which I haven’t been overwhelmingly productive and buzzing with responsibility. In the absence of excessive cortisol coursing through my veins non-stop, I think with a newfound clarity, and with much greater recall, even in the remit in which I most greatly suck. That is, the physical. For example, I withstand a chokehold quite close to the point at which I know my breathe will no longer hold out (breathe? Nope, it's not about losing breathe, it's about losing blood flow to the brain –Ed:...future Sarah) ). I tap out tactically, not in panic. Fists that used ball up in a panic under the weight of an opponent are slightly less reactive, though the bad habit of clinging to a fabric remains to be rooted out, at least in scenarios in which a Gi is absent. Sometimes, in the heat of it, I remember carefully what I need to do. I no longer just scramble- a strategy that sometimes proffers explosive results, but which is unreliable and ineffective against the strategic, clever fighters who seem to have every eventuality and future outcome mapped out to a tee. I experiment with what I am taught, even if it means moving away from the tried and tested sequence, I use time and again, and never quite complete. By completing, I mean taking mount position, and raining punches down on my opponent. Something I don’t really like to do, if I’m honest. Punching someone in the face a lot while you’re sitting on them just seems so rude. “You’re too nice,” my first coach said a fair few times. I have committed myself to the effort of really trying to retain the physiological data that is passed on to me, about maneuvers and behaviours that are unwise, algorithmic dead ends. I don’t rely so much on brute force to protect myself, and I try finally, truly, to understand the mechanics of submissions, the strategies around how to achieve and escape them. Other important points to note. It feels like I know nothing at all about this sport. I’m not sure what it was I learnt up until now, how much I might have unlearnt, how confusing it all still is, like I’m surrounded by people speaking in tongues, and I’m still not picking anything up. I am hoping, now that the backdrop of my life is considerably calmer, with almost a total absence of menace, I can focus on this learning, on learning to define and negotiate with myself the points at which I carry on, or step off from a particular challenge. I remember one thing my first coach saying about stress. There's a point at which it sharpens. After that, it takes you under. Learning to fight is about negotiating such terms bit by bit to a point where you are making accurate assessments of your own capabilities, your own staying power. It's about learning to make assured assessments that aren't so much based on the spectres you carry around with you that are inspired on whole host of fears and biases - about when you can and can't prevail - but on a reality that is as humbling as it can be empowering. One coach I had for a couple of months, who instructed in wrestling and Brazilian Jiujitsu, said, recognising that what I struggled with most was applying these intricate physical movements to stressful scenarios, that I’d just have to show up for long enough until something clicked. It still hasn’t, but I guess I’ll just carry on being thrown around and choked out until it does. "I am not a nice man, I have been fighting since I was six." I remember him saying to me of his occasional testiness, which didn't really bother me, especially as what lay beneath that felt like a strong sense of justice and honour- and which anyway kind of befitted his branding, that is, a host of photos from the Octagon, blood dripping from his lips and his fist his held high in the air. "I am not very nice. But here, you learn to work under pressure." Another thing he said, about takedowns (the movements statically most responsible for injuries) specifically, was that they actually become more dangerous if you approach them with ambivalence. "You have to commit to your takedown," he'd say. "Or it goes wrong." My first coach told me off countless times for overthinking. I asked him for research materials and he basically just said: "Nope". I always feel better after a class. Lighter somehow. Things feel a little bit more vibrant beyond the mat; I walk down the streets of Berlin with a freshness that feels like you’re 12-years-old, just out of a swimming pool, rubbing chlorine from your eyes, blinking at the midday sun. Things feel pretty, and sharp, and easy, and bright. Everything feels OK. Like worrying about anything is dumb and pointless.

It still surprises me, how much my body can withstand. The intensity of pressure it can endure, the strength and cleverness that lurks somewhere hidden until called upon to act. I think, after years wrestling with, and ultimately finding myself humbled by the limits of my mind, its nice to see, or at least, hope to see, potential expressed elsewhere. Read more on Sarah's Mixed Martials Arts journey via the links below: 1. Fight Club 2. Lessons from the mat 3. Good and bad algorithms 4. Taming the lizard brain Read her summary of why she fights, and what cultural value MMA brings in her BIO. In which the writer describes a wander into her childhood neighbourhood, and muses on the pressures of the modern newsroom, where informational downloads make navigating nebulous spaces -and a sense of living something more than a hypercerebral, hyperfrazzled existence- a challenge. I am breaking with blog tradition and writing at night time. It’s a beautiful evening, finally a bit of rain, the sky has a blueness to it that’s ocean-like, the buildings a hulking blackness broken up by sporadic glowing yellow squares. Streetlights shining against the shadows of leaves refract against my window’s glean; makes the glass look a little bit like it’s peppered with stars from a children’s book. Last week I found myself in my old neighbourhood from childhood, in sleepy Dahlem, broke my rule of not disappearing on companions to see if I could find my way back to my childhood home without checking Google Maps. I overestimated the walk by about an hour and half but found my way in the blistering heat to Bruemmer Strasse 26. Broke into the shared garden to explore. There were weird gnome-like statue things that weren’t there before, but otherwise, it seems like very little has changed at all. The old currywurst stand down the road is still there, even. It was strange being back there, but, after months of spending more time in a state of lost as opposed to found, it was kind of nice to know that something inside me was able to find my way. And, after all these years, the same McDonalds lives in the same place. Almost as if no time has elapsed at all. I’m not sure if the newsagent’s is still there, the one where our family had a standing order of around five newspapers a day; papers which still exist today - none of which have yet folded, which is nice to know. Sometimes, when I’m being good and productive, I’ll buy a weekend edition of one, bring it home, leave it sprawled out on the kitchen table, marking my territory. It’ll rest there for an hour or so until my housemate folds it up and tidies it away, returning our shared space to its barren order. Sometimes, there will be flowers in its place. From my understanding, newspaper mess does not count as mess; it makes somewhere home. Same as how the three beeps that precede BBC’s radio service aren’t so much noise as a daily reminder to be quiet, and to listen to the world. These days, though, my morning rituals are kind of different to how they were some years ago, and what I grew up with. This sounds silly and/or Daoist, but if I’m honest, I like my mind empty in these hours. I don’t want to be thinking about everything big and grand happening everywhere else. I want to be here. In my own skin, in my own body, thinking about simple and unexceptional things like breakfast and whether it’ll rain later and what kind of rain that’ll be. If I was plying my trade in the traditional sense, finding my way daily to the hellishly fantastic quagmire of modern day newsroom, where everyone is at the verge of a nervous breakdown and the coffee tastes like electric mud, I’d be forced to download large swathes of data, ideally generating out of all that increasingly incoherent informational noise a pitch or two up my sleeve, ready to rebuff whatever wisecracking-journo-bro correction is fired my way when I’ve been stupid enough to make a comment vague enough to be misconceived and misrepresented by someone desperate to appear the cleverest in the room. The other week, a journalist friend corrected me on a subject that was supposedly my area of expertise, not hers. She was so forceful and convinced about it that I conceded to her position. It was only going home, to look up stories I have in the past edited, that I was able to confirm to myself that I had actually been right.

I think many journalists like to feel and seem like they know everything. I find trying to uphold this deceit boring and exhausting. Of course, we don’t know everything. How can we? Most of us just know bits and bobs about the world that come under the, rather restrictive, (and-in-constant-need-of-reassessment), banner of newsworthy, or, like me, have a peculiar and insatiable appetite for burrowing into underexplored landscapes of knowledge and experience, such that we come out the other side having woven all sorts of strange informational threads into something pretty, interesting and informative enough to warrant being shared with a stranger. I’ve been recently reading some texts on some distinctions between fiction and non-fiction writing. In one article I came across, a novelist brings up a term coined by Keats, called “Negative Capability,” which describes a style and form of writing that does the opposite of inform. Rather, it prompts the reader to make space for, and manage discomforts around uncertainty and nuance, leading them into a state of confusion that has its own sort of charm to it which you wade through in a half light, anchoring yourself to what can hold onto while inevitably submitting yourself to the strangeness of it all. These informational downloads that I used to put myself through, which I now don’t have the stomach or the will for, or maybe what’s lacking is the drive. I’m no longer trying to keep up with peers who can sort of confidently chew down on huge chunks of knowledge and whittle them down into news segments, shouting them into the Twitter ether like a closed-circuit tribe of baboons. It felt like trying to be that person was giving away too much, like barrelling towards a certainty in ideas I don’t think I could ever have. And like being all head, and nothing aside from that. Sometimes, when I lie in bed I can hear the screeches of the S-Bahn, and it sounds like there are banshees living there among the tracks. *For the sake of accuracy, I'd like to note that the anecdote from buying newspapers and keeping them in the kitchen is a little bit out of sync with the rest of the blog, as it took place in a different flat to the one in which I now live. |

Sarah KaracsA Berlin-based writer engages in the study of belonging and in-between places after years spent faraway from 'home'. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed